Two Hours After Getting A Speeding Ticket, I Returned To The Scene To Prove My Innocence

On the day of my trial for my speeding ticket, I brought evidence that the 35-mph sign did not do its job which, consequently, should excuse my speeding violation.

About ten years or so ago, I was driving to meet with a work colleague for coffee. The route took me into a part of town with which I was less familiar, and specifically onto a road I had not driven on in a few years.

I was driving along, not speeding (or so I thought), because I was actually a few minutes ahead of pace to arrive at the coffee shop on time, according to my GPS.

Suddenly, I saw police lights strobing behind my car. I pulled over, and the police officer approached my car window. He asked me if I knew how fast I was going. I said something like...

Yes, I was going between 45 and 50 miles per hour.

The speed limit on the road, as far as I knew, was 45 mph (and, by the way, I was not lying about how fast I thought I was going: I was fairly certain that I had been going between 45 and 50 mph).

To my surprise, the officer informed me that the speed limit was 35 mph, and that I had therefore been speeding.

Puzzled, I asked the officer if he was sure that the speed limit was 35 mph, because, as I recalled aloud to him, "there are several speed limit signs along this road posting a 45 mph speed limit[,]" signs which I remembered seeing just moments before, as I traveled down that road.

The officer affirmed that I had driven past several signs along that road posting a 45 mph speed limit. But, importantly, the officer noted, the speed limit changed from 45 mph to 35 mph about 50 yards from where the officer had pulled me over. Apparently, the officer had been staking out that speed-change location, waiting for someone like me to come along.

The problem, though--as I noted to the officer--was that I did not recall seeing any signs posting a 35 mph speed limit. I only recalled seeing the signs posting a 45 mph speed limit. So, I asked the officer to specify where the speed limit changed from 45 mph to 35 mph, and how specifically I was supposed to have known about the required speed change.

The officer turned and pointed to a sign post, behind both of our cars, just beyond the last stop light I had driven through, about 50 yards back. From our vantage point, we could see the metal post, and we could see the sheet metal of the sign affixed to the post, but we could not see any lettering on the sign, because the sign's lettering was facing the opposite direction.

I told the officer that I had not seen the sign, apologized for my inadvertent speeding violation, and took my speeding ticket. After I left the scene, I went to my coffee meeting.

The Speed-Limit Sign Was Hidden

After the coffee meeting, though, I decided to go investigate further the stretch of road at which I had been ticketed less two hours before. I drove my car in the opposite direction as before, until I had driven past the location of the 35-mph sign the officer had pointed out to me earlier. I then turned around and headed back down the route in the same direction I had been heading when I had been caught speeding earlier.

My intention was to try to figure out how/why I had missed the 35-mph sign that should have alerted me to the speed limit change from 45 mph to 35 mph. What I discovered shocked me: the entire face of the 35-mph sign was hidden from oncoming traffic behind a low-hanging tree branch. You could see the post emerging from the foliage, if you knew what to look for, and where. But there was not any indication of what signage might have been affixed to the post, and there was no way to see the contents of the sign itself from the vantage point of a car driving down the road in the direction I had been heading earlier that day.

In other words, my investigation revealed that the 35-mph sign could not have alerted me earlier that day to the speed-change. Something about that fact, combined with fact that I had received a speeding ticket at that location, seemed to me to be clearly unfair. Because I was not terribly familiar with that road, I was reliant on the roadside signs to tell me what the laws were on that road.

Moreover, recall that I had mentioned to the police officer the several 45-mph signs I had seen along the road before arriving to the speed-change spot, and the officer had acknowledged the existence of those signs. So, my inadvertent speeding violation had not resulted from me just assuming what the speed limit was, in the absence of any signage along the road; instead, it had resulted from me relying on the several 45-mph signs I had seen, followed, and continued following when no other visible sign alerted me to a required speed-change.

In terms of basic fairness, it seemed plain to me that it should matter that this 35-mph speed limit sign was not visible to me that day. Was I speeding that day? Sure, that seems to be true. But should I have known what the speed limit was at that location? That seemed to be the rub for me: in my view, the answer was no, because I had no way to have known about the speed-change (due to the concealed 35-mph sign), I should not be held responsible for the 35-mph speed limit.

What I later found, though, was that this argument did not do well in court. On the day of my trial for my speeding ticket, I brought evidence of the concealed 35-mph sign, photographs and video which I had collected after my coffee meeting on the date of the violation, which showed the sign's location from the vantage point of oncoming traffic, and which showed that the concealed 35-mph sign was the first sign alerting drivers travelling in that direction of the speed change from 45 mph to 35 mph. The evidence showed, I argued, that the 35-mph sign did not do its job that day, which was not my fault, and which, consequently, should excuse my speeding violation. The judge disagreed.

On one hand, the judge acknowledged the intuitively unfair circumstances. But, on the other hand, the judge explained that, broadly speaking, the US justice system is largely designed to assume that people subject to US law (as well as the law of any of its component jurisdictions) know and understand what the law is and what their obligations are under that law. Speed limit laws were an excellent example of this. As the judge explained, you (the driver) are responsible for following the speed limit regardless of whether you know the speed limit or not.

Because this responsibility is so sweeping, it supersedes any unusual instances in which a driver might be able to truthfully claim that he/she did not know what the speed limit was. This would obviously include instances of negligence or apathy on the part of the driver, when a driver just wasn't paying attention. But it would also include instances of the road owner (i.e. the state, of the county, or the city, etc.) totally failing to do its job to post ample, and visible, signage, to reasonable alert drivers of the lawful speed limits on a given road.

[P]ersonal responsibility is good for society, and underlies not just our legal system, but our lives. How should society go about encouraging personal responsibility and its corollary, discouraging irresponsibility? One simple answer is to "set irresponsible people free."

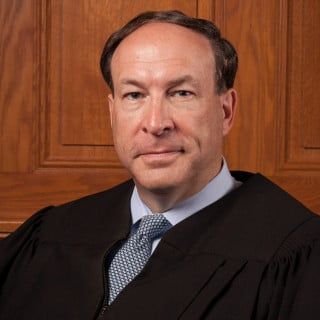

--Judge Michael B. Brennan, excerpted from The Lodestar of Personal Responsibility

This is one of those "corner cases" that stands, I think, in exception to the virtue of the default rule: of making people personally responsible for their actions with regard to the law. What my experience taught me was that...

- the justice system will hold you responsible for your unlawful actions (e.g. speeding),

- even when your unlawful actions were not known by you to be unlawful (i.e. when you think you're going the speed limit but are mistaken),

- and even when your unlawful actions were at least in part (if not entirely) due to the irresponsibility of some third-party whose job it is to keep you apprised of your lawful obligations (e.g. the road owner, whose job includes posting sufficient speed limit signage, and then maintaining that signage, to ensure that the signage remains visible to affected parties).

Parallel Lessons For Civil Law

There are many corner cases like this in the US, and not just on the criminal side. On the civil side, for example, it's common for a buyer of a product or service to sign a contract (pertaining to the purchase) that was prepared exclusively by the seller.

Because most people do not read every word of a contract before signing it, sellers would have a dangerous advantage in that scenario. A buyer might "rely" on a seller's representations, for example, as to what a contract actually says (or does not say) or as to what a contract's content actually means (or does not mean), legally speaking, for the buyer. If the seller gives the buyer incorrect information at that moment, then the buyer may later find himself locked into a contract containing less favorable terms than the seller had led the buyer to believe.

How would a court adjudicate contract dispute that later followed from such a scenario? It's probably not as "fair" as you might think, which is how/why it parallels my experience with the speeding ticket. Sure, the court may consider issues of misrepresentation by the seller, and how those might have affected the buyer's decision making. But you would be surprised to learn how narrowly a court might such "misrepresentations" a given buyer might allege. For example, if a buyer merely stated that the seller gave the buyer incorrect information as to the buyer's legal rights under the contract, then a court might not consider this "actionable" misrepresentation, especially to the extent that a buyer had relied on the seller's statements in lieu of the buyer making any separate attempt of his own to try to read and understand the contract and its legal implications. The court might explain this decision by the buyer as negligent or imprudent. But nonetheless, US courts tend to hold contractual parties responsible for the terms of a contract into which they freely enter, even if one party did not understand those terms at the time the contract was executed.

Is that "fair?" As with my speeding ticket example, the answer to that question may end up being legally irrelevant, given the US justice system's bent toward personal responsibility. This is why it would, in theory, behoove you to always know as much or more about your legal rights than anyone else you encounter--whether it's a police office who pulls you over for speeding, or a salesperson trying to get your signature on a contract.

Because such an ideal is, practicably speaking, often unattainable, it's useful to have quick/easy access to someone/something who knows more about one or more aspects of your legal rights than you do. Traditionally, this "someone/something" was almost exclusively (if not entirely exclusively) a card-carrying lawyer. But, fortunately, nowadays, you often have more than one option (e.g. software, consultants, and even internet forums in some cases).